Mary I: Life Story

Chapter 8 : Wyatt's Rebellion 1554

Mary's heart was set on a marriage with a foreign prince, partly for reasons of prestige (why would she marry a subject?) and also because she wanted to reinvigorate England's position as a member of the wider Catholic, European Christendom. She was concerned, too, about the actions of France.The French heir was betrothed to the young Mary, Queen of Scots, who had a good claim to the English Crown – under common law, if Elizabeth were discounted on the grounds of illegitimacy, then the Queen of Scots would be Mary’s heir.

After five centuries during which English history has perceived Spain as the enemy in the sixteenth century, it is hard to remember that, up until the reign of Elizabeth, Spain had been seen generally as an ally against the French and so, for Mary to look to Spain for alliance was not surprising, leaving aside that her own parents’ marriage had been a manifestation of it.

Although initially Mary said she would have preferred an older man, she soon became persuaded that the most appropriate husband was Philip, twenty-seven years old and the son of her cousin, Emperor Charles V. Charles, although widowed, ruled himself out. He had been betrothed to Mary when she was just a child, and had supported her from a distance over many years, but tired, gouty and looking forward to abdicating, he put forward his son instead.

Mary was determined to have her way, despite misgivings among her Councillors – although none of them was so averse to the match that he couldn't be bought with a pension. Philip was heir to Spain, and the Low Countries, and the marriage treaty provided that any heir Mary bore would inherit England and the Low Countries - this would have been a huge benefit, had it come to pass, as Burgundy was England's biggest trading partner. Mary also made it clear that even after marriage, she would remain as sole monarch, and would not permit her husband to take any official part in government, although it is probable that most men doubted her on this.

A deputation from Parliament, tipped off by Gardiner, who supported a match with Courtenay, requested an audience from the Queen, in which they begged her not to marry a foreigner, lest he try to either take her abroad, or, in the event of her death, usurp the throne.

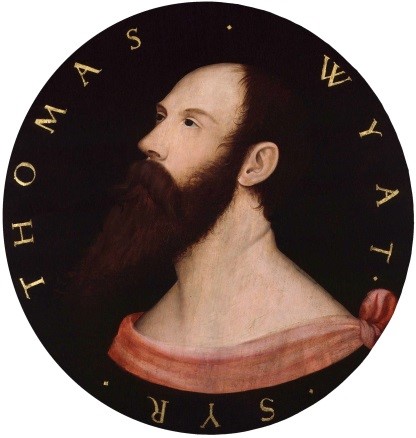

Mary was outraged by this interference with her royal prerogative and sent them off with a flea in their ear, taking Gardiner to task for putting them up to it. But she might have done better to listen. As soon as the proposed marriage became public knowledge, it stirred murmurings of discontent. Fear of foreigners was rife, and, amongst a vocal minority of Protestant gentry, this led to open rebellion, headed by Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger. Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, was also involved.

Wyatt claimed that his aim was just to prevent the match with Philip, but most people believed it was to replace Mary with either Jane Grey or Elizabeth, with the latter to be married to Courtenay. Courtenay himself was involved, but it was his revelation of the plot to his mentor, Gardiner, that enabled the government to take preventative action to scotch part of the planned uprisings through the capture of Suffolk

Although isolated, Wyatt went ahead, and marched on London from Kent with a sizeable army. Mary, displaying her usual qualities of personal courage, iron determination and decisiveness in dangerous situations, reacted immediately. She called out her troops and, refusing to flee in the face of rebels heading for her capital, rode to the Guildhall and made an impassioned speech, defending her rights to the Crown and her determination to undertake the marriage only if it were of benefit to her people and consented to by Parliament. The rebels were defeated and Mary was safe.

Unfortunately, Jane Grey was not. Persuaded that as long as Jane lived, there would be uprisings in her favour, and also that Philip would not be arriving as long as there was any danger, the sentence of execution against Jane and her husband was carried out. Mary was clear that, if Jane accepted the Catholic faith she would be spared but Jane, just seventeen, would not renounce her faith.

Jane dispatched, the attention of many was diverted to Elizabeth. As before, Elizabeth had given no indication whatever of support for the rebels - but nor had she given much show of loyalty to Mary. There was evidence that potentially incriminated her - letters sent, that she denied receiving, and arrangements made for her to go to a particular house that, on being questioned, she denied remembering she even owned. Elizabeth was sent to the Tower of London, whilst the evidence was examined.

Mary, although she had reluctantly accepted that Jane's death was necessary, was adamant that Elizabeth could not be convicted without solid proof. None was forthcoming, so, eventually, Elizabeth was sent from the Tower to house arrest at the old palace of Woodstock in Oxfordshire. Her guardian, Sir Henry Bedingfield, was the son of the man who had been Katharine of Aragon’s guardian at Kimbolton Castle – presumably a deliberate choice. Nevertheless, Mary gave orders that, although Elizabeth was to be ‘safeguarded’ she was to be treated with the proper respect due to her position.

Meanwhile, Mary had achieved, on paper at least, one of her objectives. Parliament, chastened by the suppression of Wyatt’s rebellion, and partially, if not wholly, reassured by the very favourable marriage treaty, ratified the Queen’s marriage to Philip. It was reaffirmed that Mary was, and would remain, the only sovereign. It was also confirmed that England would not be expected to involve itself in Philip’s Italian Wars, nor could Philip make any political appointments, whilst any power he held would be relinquished on her death. It was expected, however, that he would influence Mary, and, to an extent, he did.

Marriage to Philip

Philip himself was not particularly eager for marriage to Mary. She was some eleven years older than him and he already had an heir from an earlier marriage (the mental health issues of his son, Don Carlos were not yet apparent). Nevertheless, he was an obedient son, and in the summer of 1554, he sailed for England, armed with detailed advice as to how he should ‘caress’ Mary’s nobles and a warning that none of the soldiers on the fleet delivering him should be permitted to come ashore, lest it give weight to the French King’s hints that Spain intended the conquest of England.

Philip arrived to a lavish, but rain-soaked, reception. Mary met her bridegroom privately two nights before the wedding. They talked for about an hour in front of the court – he speaking Spanish, she replying in French, although she taught him quickly to say goodnight to the company in English.

Mary and Philip were married at Winchester Cathedral on 25th July 1554, with the ceremony conducted by Gardiner, flanked by five other bishops.In order for Philip to have kingly rank, other than as Mary’s husband, Charles had abdicated the Kingdom of Naples to him. Following the ceremony, they were proclaimed as Philip and Mary, Kings of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, Ireland etc etc through a vast list of Princedoms, Archduchies and Lordships.

The royal couple returned to London, where, on the surface, the match was greeted with becoming rejoicing – pageants being prepared showing their union as a coming together of two descendants of Edward III, and portraying them as givers of justice and equality. Under the surface, however, anti-Spanish tensions ran high.

Mary I

Family Tree